In conversation with Xhosa Cole on the Pan-African nature of jazz, the importance of looking back to move forward, and the capacity for activism and rejoice through music.

For Xhosa Cole “Jazz music is Pan-African music by definition.” The Birmingham born saxophonist and flautist is on the line from his hometown to talk about six duets with master percussionists from the African diaspora and is taking a break from his practice to speak to Pan African Music. Winner of the prestigious BBC Young Jazz Musician of 2018, Cole has quickly established himself among the long legacy of Birmingham Saxophonists that includes Soweto Kinch and Shabaka Hutchings, and remains rooted in the historically musical neighborhood of Handsworth. Described by dub poet and another son of the postcode Benjamin Zephaniah as “The Jamaican capital of Europe” – Handsworth is the diverse inner city community that produced roots reggae band Steel Pulse and singer-songwriter Joan Armatrading, and for up-and-coming composer Cole the community was his conservatoire along with a multitude of muses including geometric maths, biology and Yoruba Culture.

“I first started involvement in the arts with a dance company here called ACE Dance & Music which stands for African Cultural Exchange” begins Xhosa. This community outreach project helped form: “a connection to the drum and a connection to dance” that Cole is exploring in his forthcoming collabs.

Sitting around the dinner table of Nigerian master drummer Lekan Babalola, the idea of these Pan-African musical conversations took shape. Musical elder Babalola kept time for artists as different (and demanding) as Fela Kuti and Prince, and was a member of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. Sharing a Grammy for his appearance on Ali Farka Touré’s 2005 album InThe Heart of The Moon, Babalola’s musical CV sounded “scary!” to Cole but the convivial family atmosphere in the home felt familiar.

Being around artists who have helped do much of “the groundwork” underscores this project for Cole, and connecting with “a diaspora that is so wide and so different but with a lot of commonality even after 500 years and many miles removed” happens as meaningfully around the dinner table as it does on the bandstand.

For this Pan-African project he will be working with Adriano Adewale, a percussionist from Sao Paulo deeply rooted in Afro-Brazillian culture. Adewale who reclaimed his name from the Yoruba meaning “royal child that came back home” plays a Pan-African setup of percussion instruments including pandeiro and half calabash.

A New Orleans native and a member of Wynton Marsalis’ Jazz at Lincoln Centre band, Herlin Riley is another part of the jigsaw. From a distinguished bloodline of New Orleans’ musicians, Riley also sat behind the drums for Ahmad Jamal. Whilst closest to home, Xhosa’s older brother will appear on one of the duets which Cole describes as “exploring new and yet old territories.”

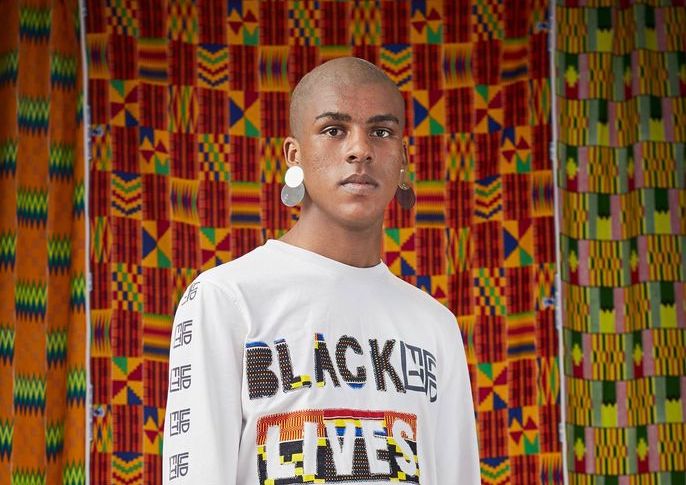

Another current project for Cole is a multimedia response to the resurgence of The Black Lives Matter movement in 2020. Working with talented animator Shiyi Li, Cole has created Stationary Peaceful Protest an animated film that arose out “of the necessity to express something that was happening inwardly” in responce to the “visceral” experience of witnessing George Floyd’s murder on the news.

Commissioned by Birmingham Symphony Hall as part of a commitment to “turn up the volume” on Black artists – the film is Xhosa’s personal response in music, spoken word and moving image, and was a source of learning for the saxophonist. “I realised how editorial I am!” says Xhosa who observes that performing improvised music on stage is a very different act of creation.

Working with Shiyi Li in pre-production allowed Xhosa to explore each and every detail such as the “apparently mundane” dilemma of what to wear to the Black Lives Matter protest. Cole recalls how he asked himself: “Do I wear a hoodie or a suit? and what is it to `look black’ anyway?” before going on to say: “There’s a whole lineage of suit wearing among jazz musicians or if you look at photographs from the arrival of The Windrush. The people look immaculate! But was that (and is that?) in some ways an assimilation of what it means to be prim and proper? To be White?” Even more existential questions are considered in the film as Xhosa narrates another dilemma of that day “I wonder about bringing my sax? If I don’t play my horn with, to, and for my community then why do I ever play my horn?”

It turns out Xhosa Cole gives most things a good amount of thought, and discussing the buzz around the much-talked about “London jazz scene”, the young saxophonist is honest about achieving success at a young age: “We have to work actively hard in this community not to be pulled through into a slipstream of promotion that puts you on a pedestal, because with that comes a sense of leniency which can correlate with resting on your laurels.” For Cole and his peers there is a constant pressure “to produce content, engagement and retention.”

That said, Xhosa Cole is prolific. Cole’s debut album K(no)w Them, K(no)w Us should be out in July. The title is an expansion on Dizzy Gillespie’s famous quote about Louis Armstrong in which the trumpeter replied that without Armstrong (K(no)w him) there would be no Dizzy. “Without our predecessors we don’t exist man” affirms Xhosa, explaining “The album is a homage to my idols, heroes and teachers. From teachers at school, to teachers at after school clubs, those teachers I’m learning from now, and my teachers on the records I’m listening to.” For Cole one of the joys and beauties of being involved: “in this thing called jazz” is “that it can serve many purposes with the capacity to be anything, to be rejoiceful or to be political.”

Before returning to his practice Xhosa Cole returns to the first theme of our conversation, the Pan-African DNA of the music we call jazz: “Jazz musicians are always ten steps ahead of the game” he quips “because they’ve looked back to go forward.” And with that, it’s back to his horn.